How AI generates images? Why is an AI generation called “Diffusion”?

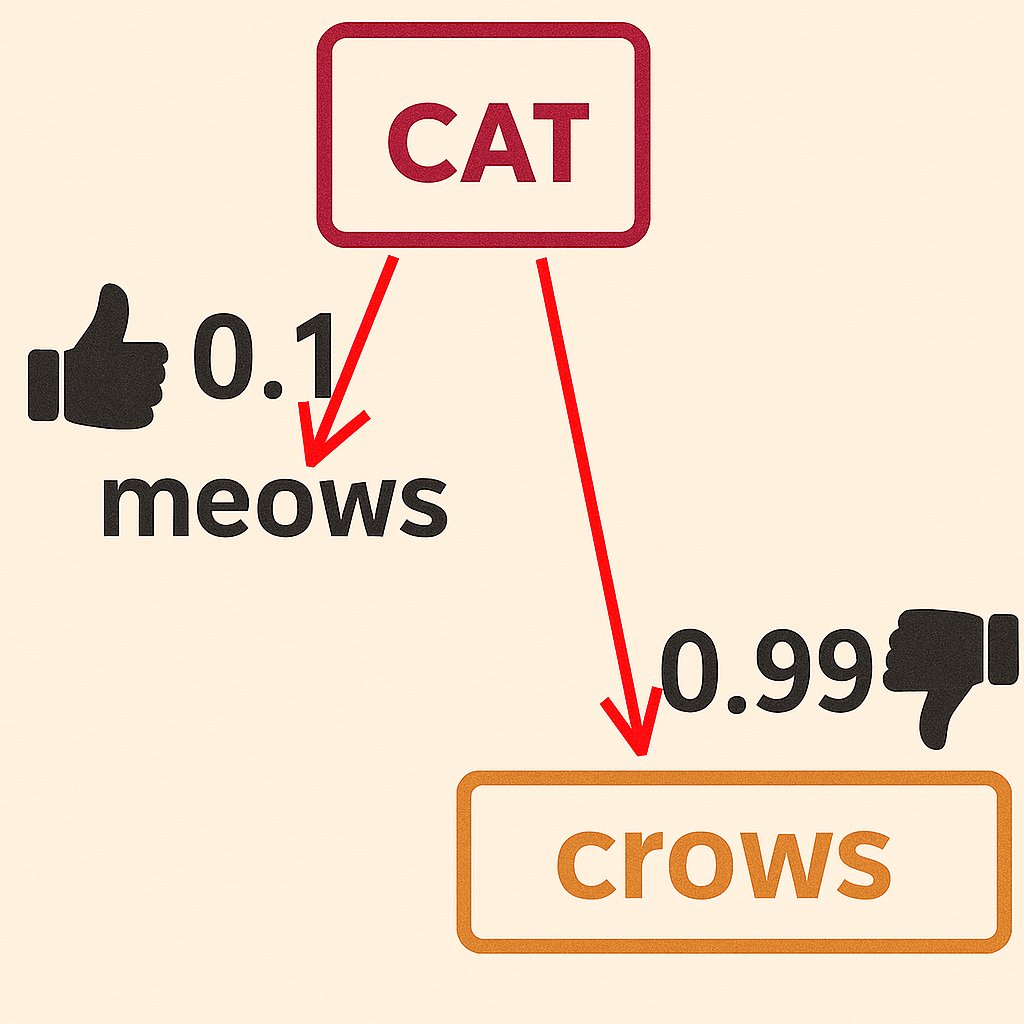

If you have read the article “What Does ChatGPT Do and Why Does It Work? A Look Under the Hood at the Magic of This Neural Network”, you already understand how AI generates text. In short, AI takes a user’s prompt and searches for the most statistically likely words related to the specified topic. For example, if you write “black cat”, AI will continue with “the black cat meows” because “meows” is a word that frequently appears near “cat” in the training texts. It will not write “the black cat crows” because such a combination of words does not appear often (if appears at all) in the texts of human language on which it was trained.

But how does AI creates impressively detailed and realistic photos and videos from a text prompt? What set of pixels corresponds, for instance, to the phrase “online news”? Yet, any diffusion-based AI model can easily generate an image from that very phrase. To create multimedia content, AI systems use clever techniques — for example, they reverse the flow of time.

Vectors in AI: explained simply

When the conversation turns to artificial intelligence, one immediately encounters the terms vectors and vectorization. There is no need to panic if you last heard about vectors in school or university — you will not need math to understand the concept.

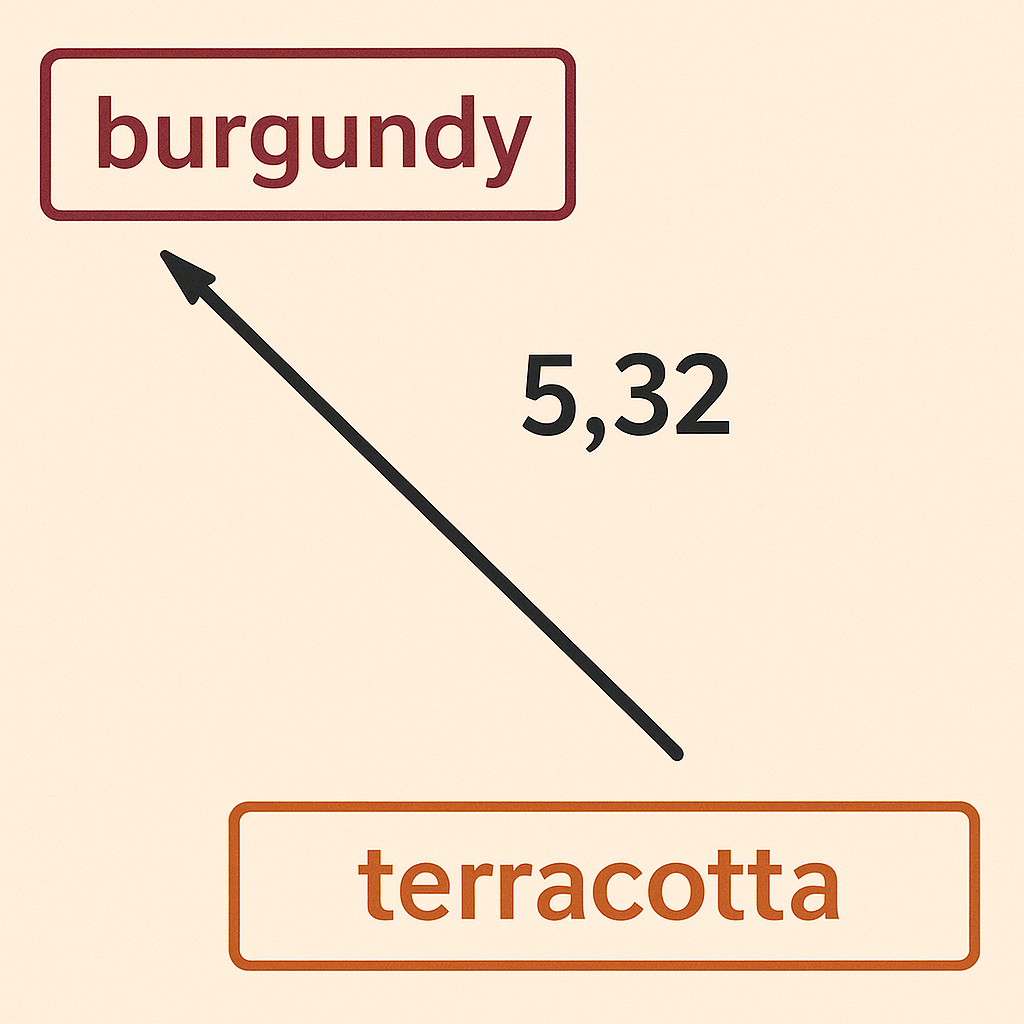

All you need to know is that a vector is simply a line with a direction. Mathematicians draw it as an arrow.

Think of it this way: all mathematics and all numbers are merely ways to measure distances between entities. You would not find it strange to say, “The distance between Kyiv and Kharkiv is 400 kilometers.” Someone took a ruler and converted the distance on the planet’s surface into a short number.

The same can be done for other entities. For example, what is the distance on the color spectrum between maroon and terracotta? You could place a colorimeter on each shade and get a numerical distance between the two colors.

When AI is trained, it builds a map of distances between all the entities it encounters. For instance, the distance between the word “cat” and “meows” might be 0.1, while the distance between “cat” and “crows” might be 0.99. Since “meows” is much closer to “cat”, AI chooses it instead of “crows”.

Fine print with asterisk: It is just for visual representation on the image, a vector value of 0.1 is considered a close connection between entities.

In actual AI systems, the distance is measured in reverse. A value close to 1 means two entities are highly related, while 0 indicates the greatest possible distance — meaning entities have nothing in common.

Every word has a similar set of distances to all others. Each such set is referred to as a dimension. And in professional terms the complete collection of these sets (i.e. dimensions) for such map of distances between entities is referred to as vector spaceorembedding space.

Now we can dive into how AI turns words into pixels.

How an AI image and video generator works

The very name diffusion model for AI image generators is deeply connected to physics. The generation of images and videos we see today works on a principle known as diffusion.

This process is remarkably similar to Brownian motion observed in nature, where particles move chaotically. However, AI performs diffusion in reverse — it moves backward in time, from the end to the beginning.

This link to physics is not just a poetic analogy. It directly leads to the algorithms that enable image and video generation, and it provides intuitive insight into how these models function in practice.

Before exploring the physics behind it, let us look at how an actual diffusion model works.

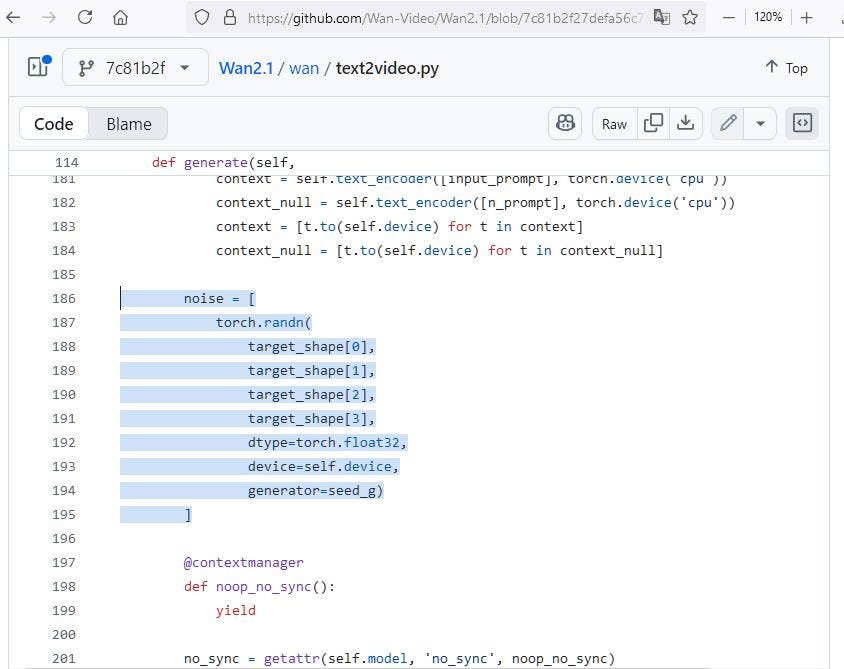

If we examine the source code of a diffusion AI generator like WAN 2.1, we find that the process of creating a video begins with generating a random number.

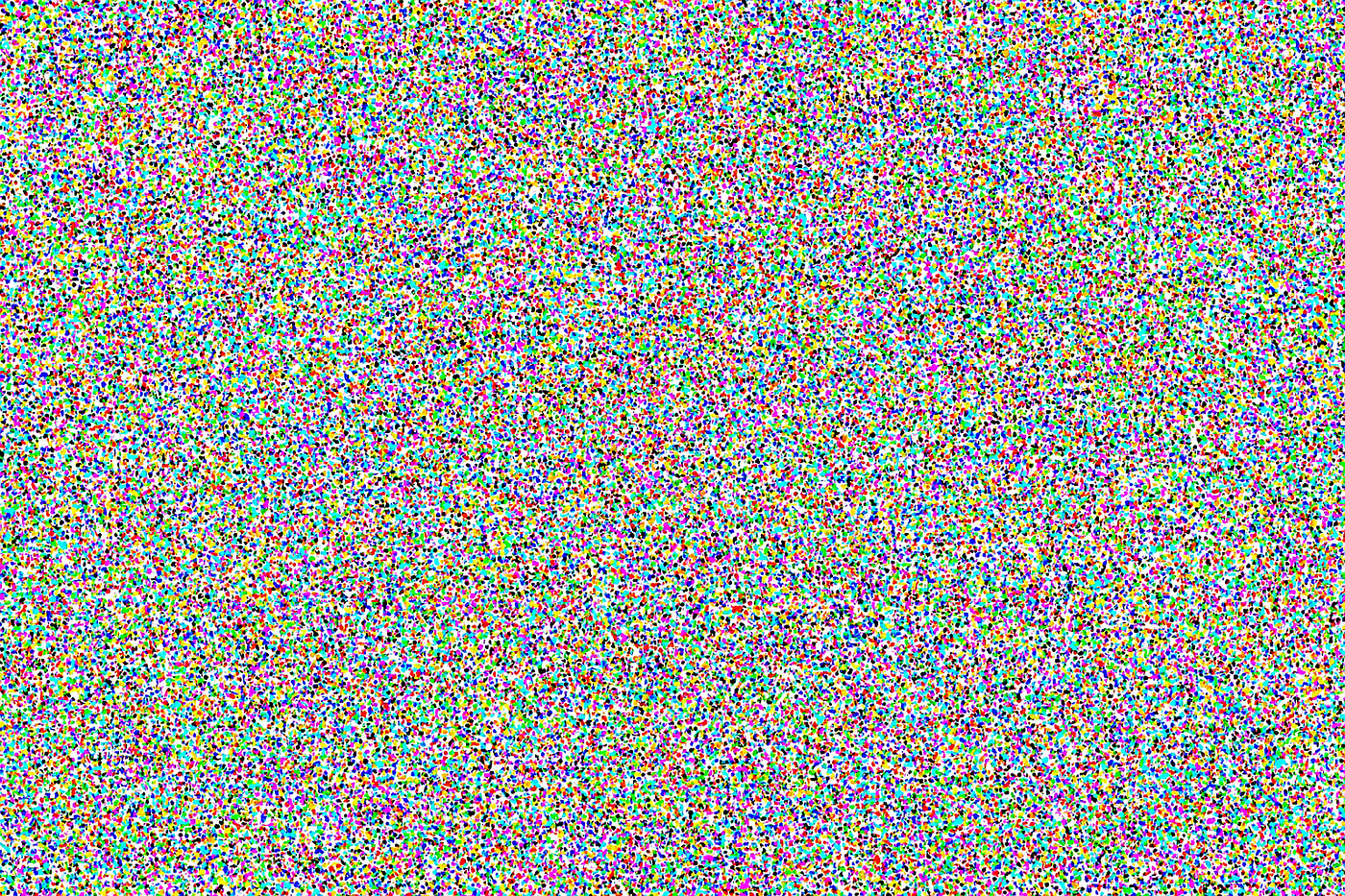

In other words, AI first produces a random set of pixels using that number as a seed. The image looks like pure noise.

This noisy video is then passed through a model known as a transformer — the same type of model that underlies large language systems such as ChatGPT.

But instead of text, the transformer outputs another video — one that already shows hints of structure. This new video is combined with the previous one, and the result is fed back into the model.

This cycle repeats dozens of times. After tens or even hundreds of iterations, the pure noise gradually transforms into an astonishingly realistic video.

But how does this relate to Brownian motion? And how does the model so accurately use text prompts to turn noise into a video that matches the description?

To understand that, let us break diffusion models into three parts.

CLIP and how AI “understands” meaning

The year 2020 was a turning point for language modeling. Research on scaling neural networks and the emergence of GPT-3 demonstrated that “bigger” really does mean “better.”

Large AI models trained on enormous datasets began to exhibit capabilities that smaller ones simply did not possess.

Researchers soon applied the same ideas to images.

In February 2021, OpenAI introduced a model called CLIP, trained on 400 million “image-caption” pairs collected from the internet.

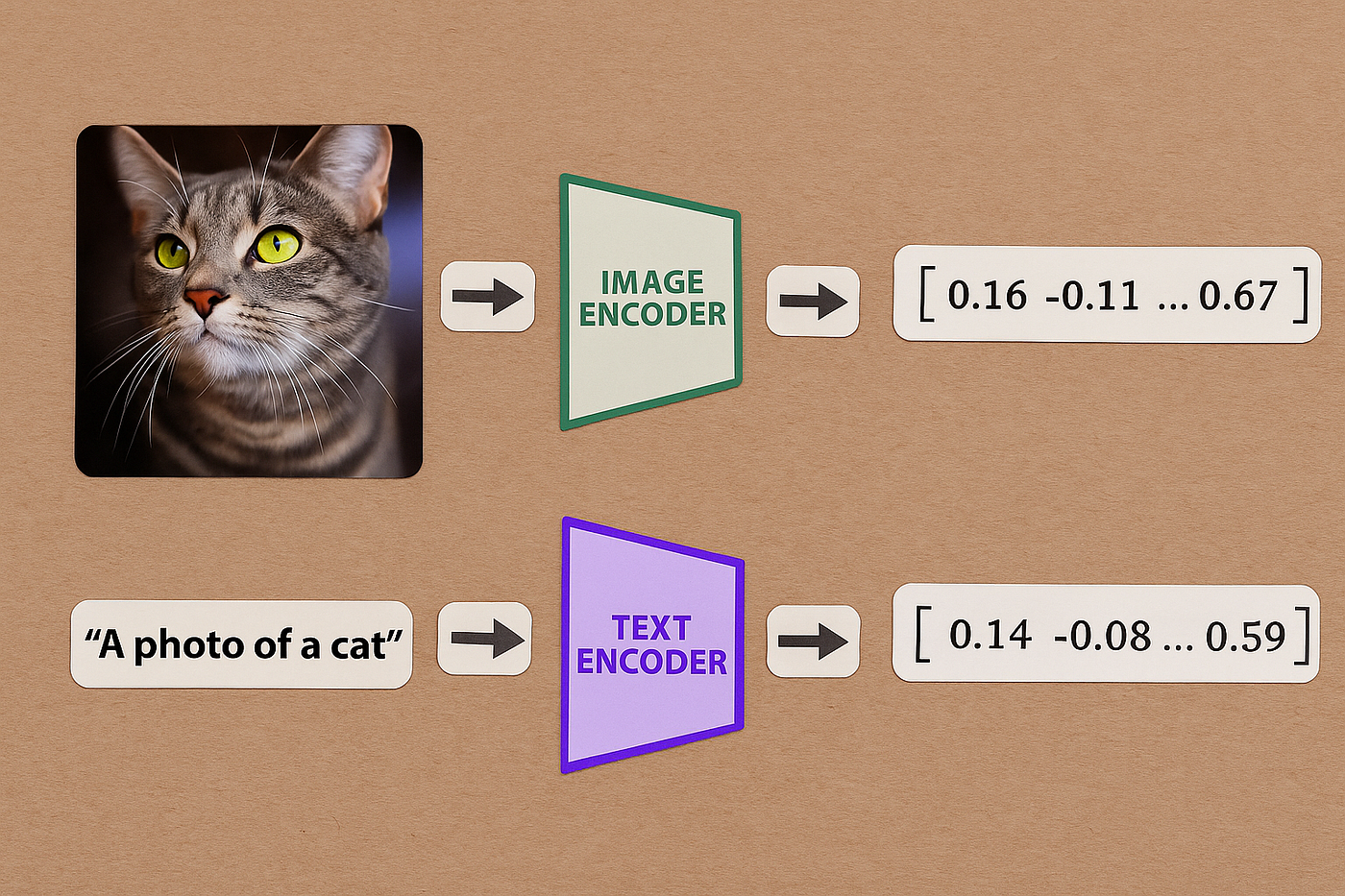

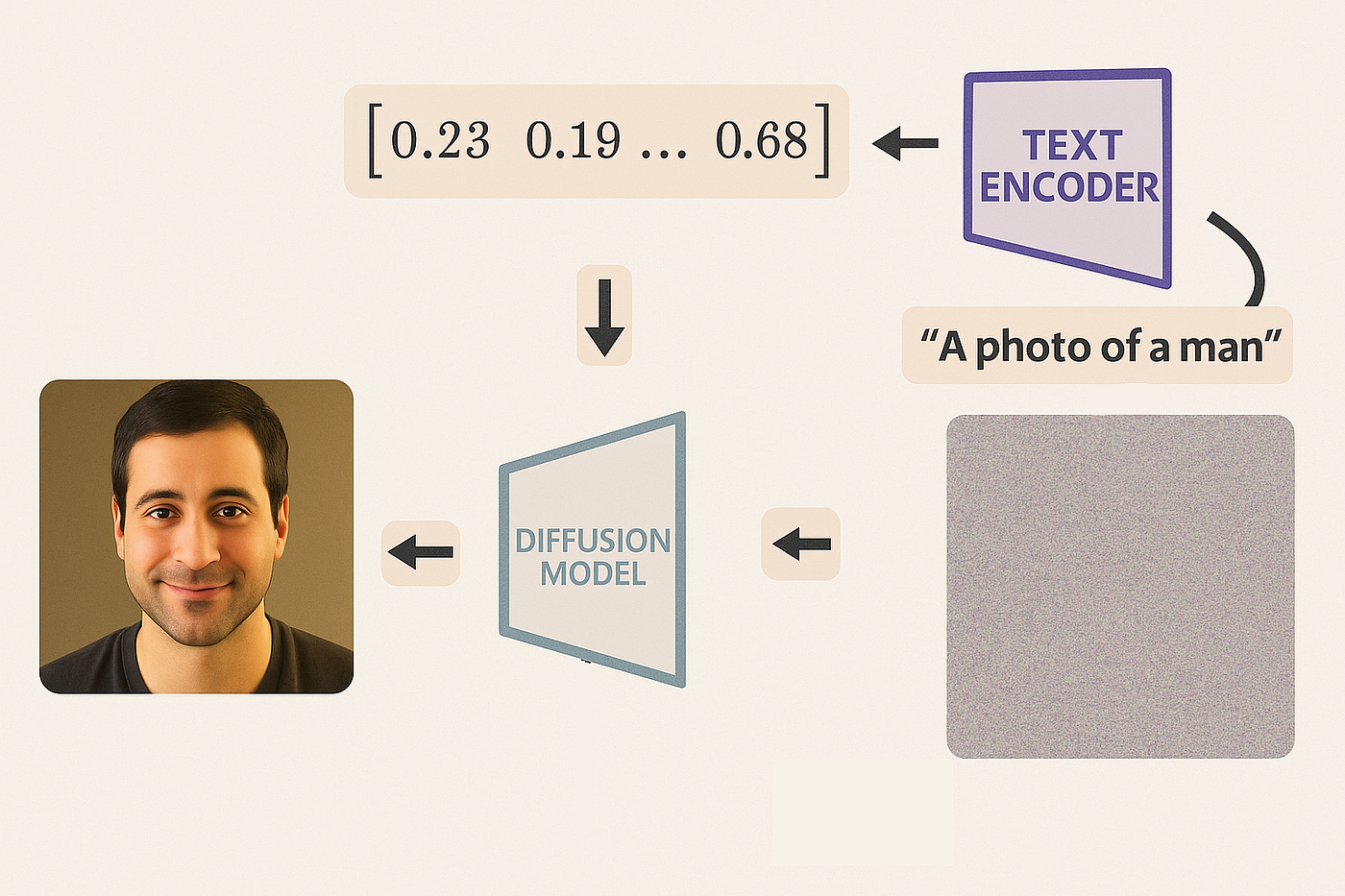

CLIP consists of two models: one processes text, the other processes images.

Each model outputs a vector of length 512, and the core idea is that the vectors for a matching image and caption should be close to each other.

To achieve this, a contrastive training scheme was used.

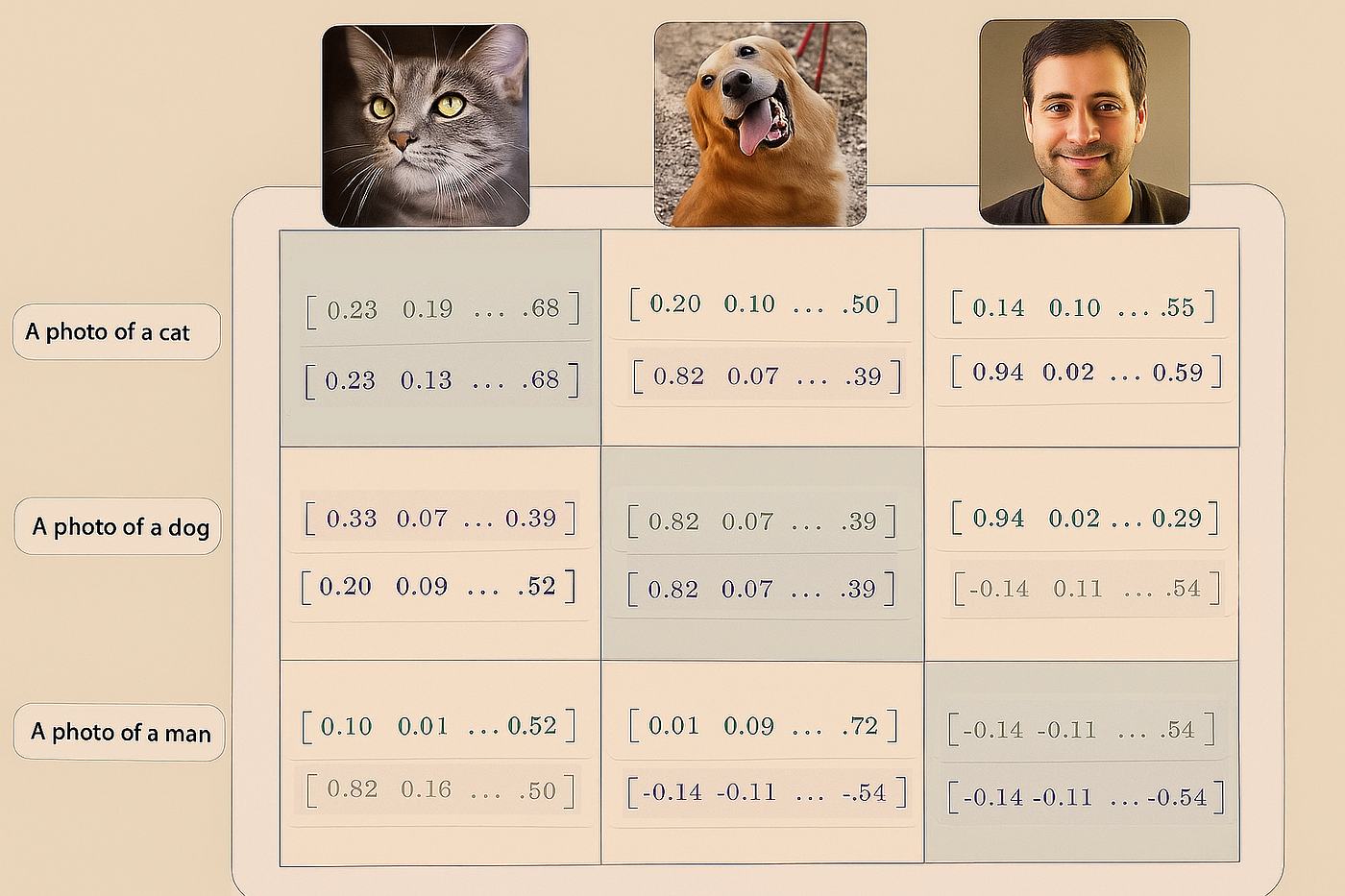

For example, a dataset might contain photos of a cat, a dog, and a man, with captions “photo of a cat”, “photo of a dog”, and “photo of a man”.

The three images go into the visual model, and the three captions go into the text model. We get six vectors (numerical distances with direction) and want the matching pairs to be most similar — that is, to have the smallest distance.

Not only are matching pairs compared, but also all mismatched combinations.

Imagine placing the image vectors as columns in a matrix and the text vectors as rows. The pairs on the diagonal are correct matches; those off the diagonal are incorrect ones. CLIP’s goal is to maximize the similarity of correct pairs and minimize that of incorrect ones.

This contrastive learning gave the model its name: Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training (CLIP).

Similarity is measured with a familiar school formula — the cosine of the angle between two lines (vectors). If the angle between two vectors is zero, their cosine equals 1 — that is, maximum similarity.

Thus, CLIP learns so that related texts and images “look” in the same direction in the shared space.

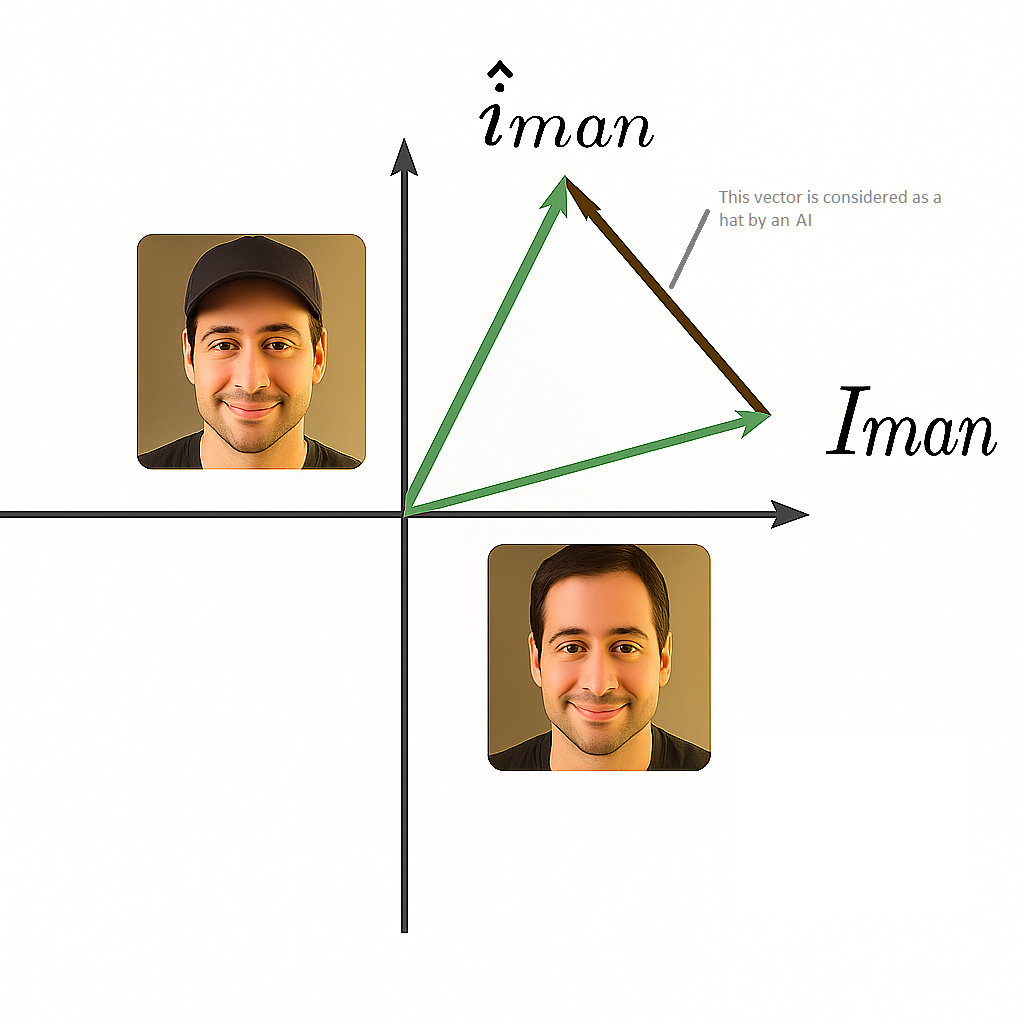

Once AI knows the distances between entities, it can manipulate them. For example, if you take two photos of the same person — one with a hat and one without — and compute the difference between their vectors, the result represents the concept of a “hat.”

By adding or subtracting these distance vectors, AI can work with abstract concepts rather than just images.

CLIP can also classify images by comparing their vector distances to those of possible captions and choosing the most similar one.

In this way, CLIP creates a powerful space that links images and text. However, it only works one way: from data to vectors, not the other way around.

Diffusion AI models

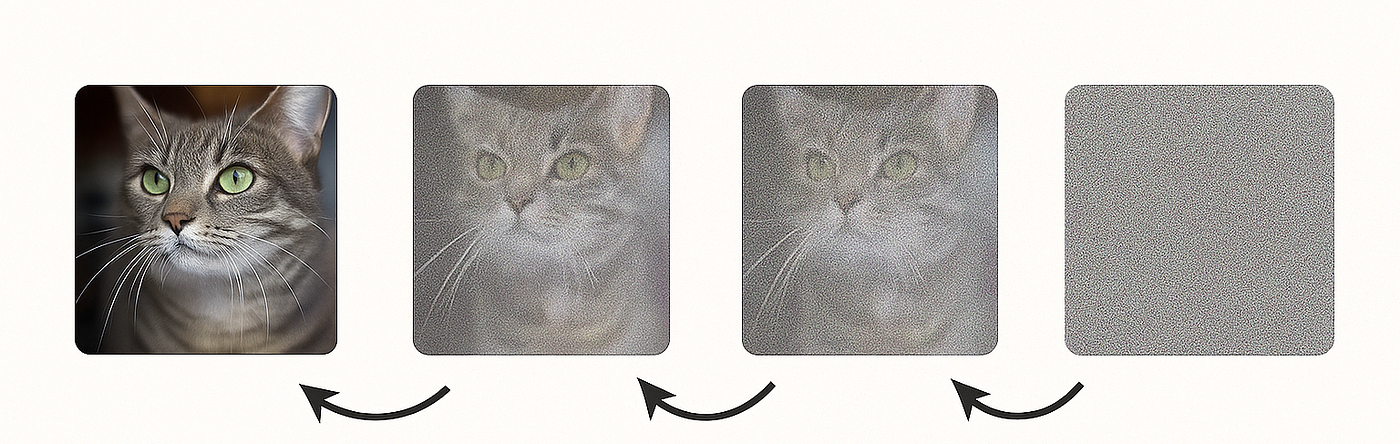

In 2020, a team from Berkeley published Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPM). This work demonstrated that it is possible to generate high-quality images by gradually turning noise into an image, step by step.

The idea is simple: take a set of training images and progressively add noise until they are completely destroyed. Then train the network to reverse the process — to remove the noise.

However, a straightforward “step-by-step denoising” method performs poorly. The Berkeley researchers proposed a better scheme: start with a clean image, corrupt it, and then reverse the process from noise back to the original image.

This method works far better than gradual restoration.

It is also important that during generation, the model reintroduces noise at each step — this helps make the results sharper.

The explanation lies in the theory of Brownian motion: adding random noise helps avoid all points collapsing toward the center of the data distribution and instead preserves diversity.

As a result, instead of a single blurry average image, we get a variety of realistic possibilities.

How AI creates images: by running time backward

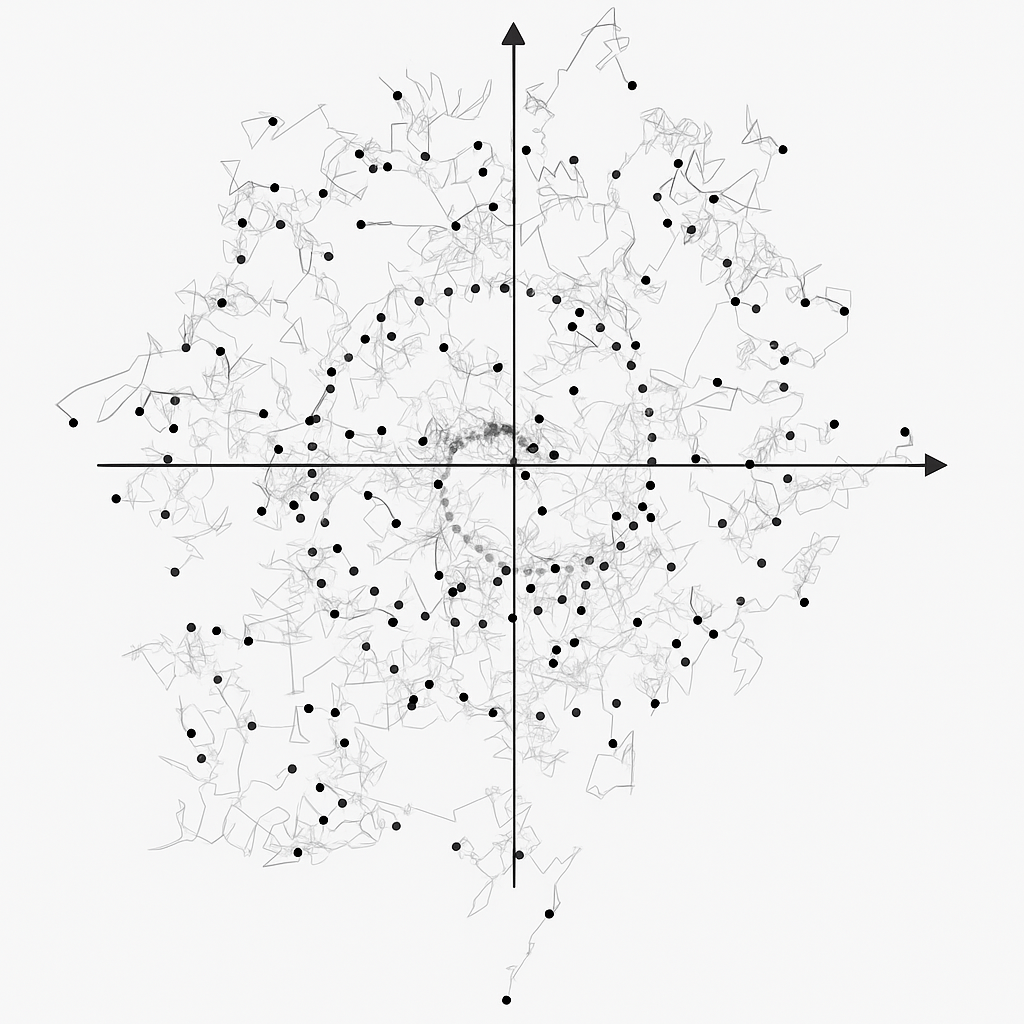

Diffusion models can be viewed as training a time-dependent vector field that tells the model in which direction to move from noise toward data.

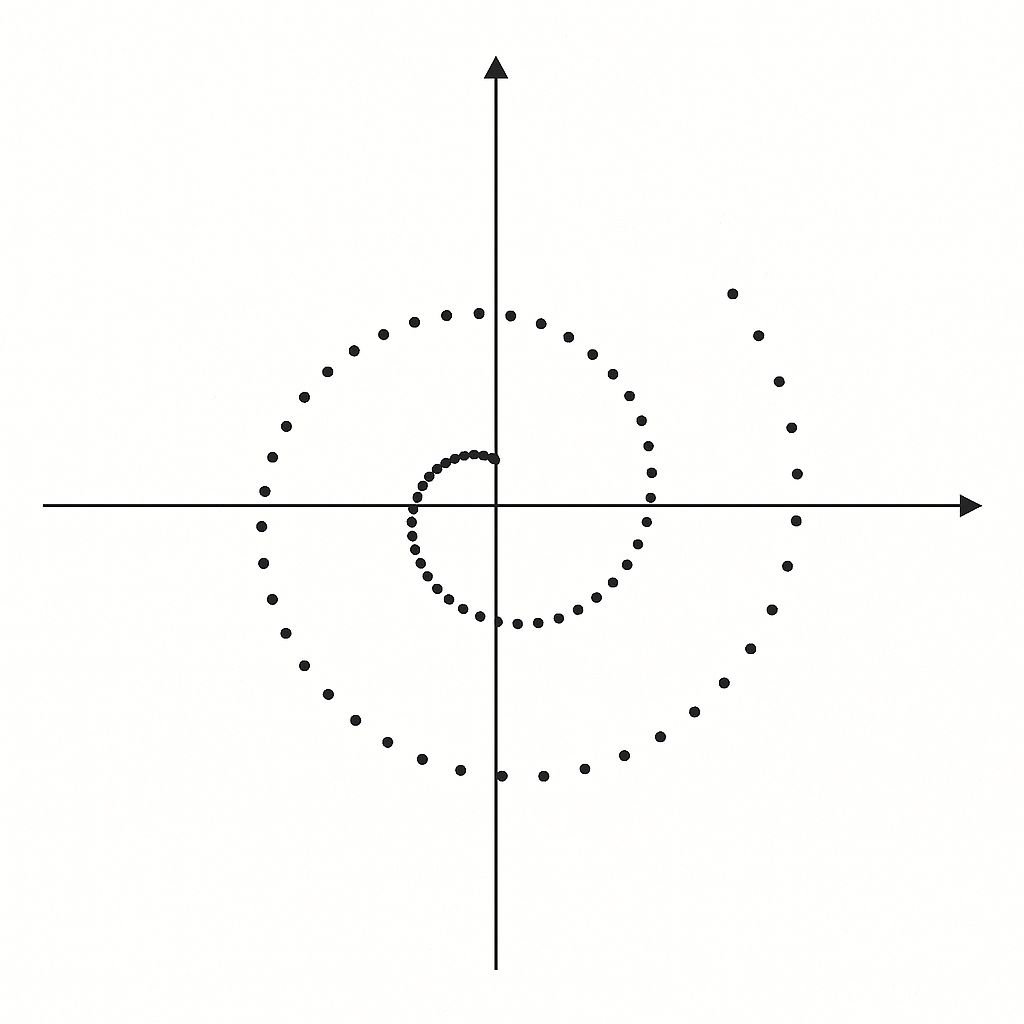

Imagine a two-dimensional example, where each point is a small two-pixel image. As we add noise, the point moves randomly — that is Brownian motion.

The model learns to “turn back the clock,” moving points back toward their original structure (for example, a spiral).

If we train it not only by coordinates but also by time t (the number of steps), the model learns to behave differently at different stages — coarse at first, then more detailed.

This makes it far more efficient.

Adding noise during generation also follows from this idea: it prevents samples from collapsing into a single average result and instead spreads them evenly across the data distribution.

Without noise, the model converges toward the center — producing a bland, blurry image.

DDIM

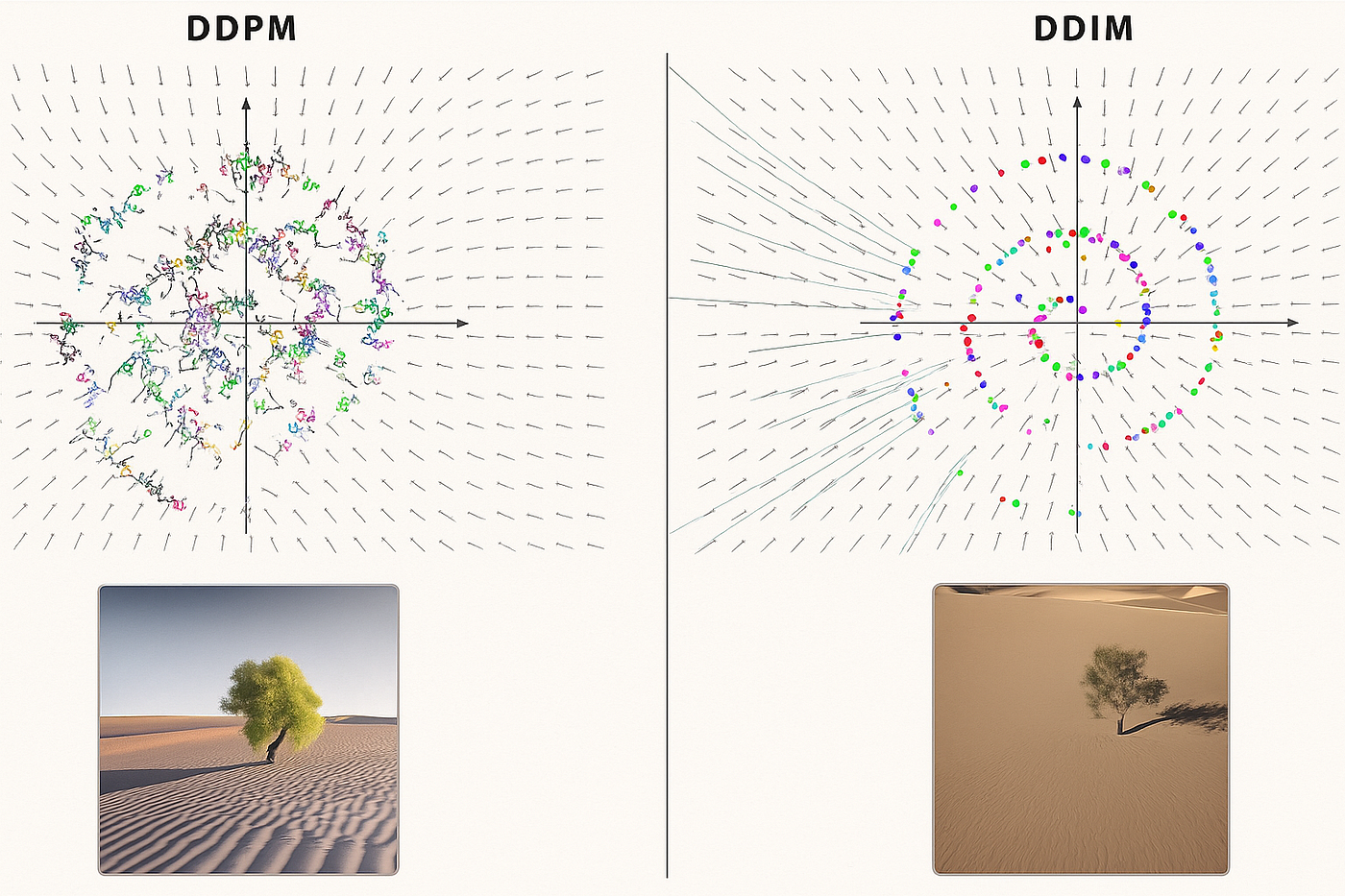

A simplified approach soon appeared: Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models (DDIM), which showed that the same quality can be achieved without random steps.

It relies on an analytical connection between a stochastic equation (with noise) and a deterministic differential equation (without noise).

DDIM allows faster generation without sacrificing quality.

Both DDPM and DDIM lead to the same distribution of results, but DDIM does it deterministically, without randomness.

WAN uses a further development of this concept known as flow matching.

DALL·E 2 and the Fusion of CLIP with Diffusion

By 2021, it was clear that diffusion models could generate high-quality images but struggled to follow text prompts accurately.

Combining CLIP and diffusion seemed natural: CLIP could link words and pictures and guide the diffusion process.

In 2022, OpenAI did exactly that by creating unCLIP, the commercial version of which is known as DALL·E 2.

DALL·E 2 learns to convert CLIP vectors into images with remarkable precision.

The text vectors are passed into the diffusion model as an additional condition, which it uses to remove noise according to the textual description.

This technique is called conditioning — conditional control.

However, conditioning alone does not guarantee full alignment with the prompt. Another technique is needed.

Guidance

Returning to the spiral example, if different parts of the spiral correspond to different classes (people, dogs, cats), conditioning helps but not perfectly — the points still mix.

The solution is classifier-free guidance. The model is trained both with and without class conditioning.

During generation, we compare the vectors for the conditional and unconditional models. The difference between them indicates the direction toward the desired class, which can be amplified by a coefficient α (alpha).

As α increases, the model reproduces the desired objects more accurately — for example, a “tree in the desert” finally appears and becomes increasingly realistic.

This principle is now standard in modern diffusion models.

WAN goes even further by using negative prompts.

This means the user can explicitly specify what they do not want to see in the image or video (for example, “extra fingers” or “motion in reverse”), and these factors are subtracted from the result.

And some words before you close this page

Since the publication of DDPM in 2020, the development of diffusion models has progressed at extraordinary speed. Today’s systems can turn text into video that seems absolutely realistic.

The most impressive part is how all these elements — text encoders, vector fields, and reverse diffusion processes — fit together so precisely that they form a coherent mechanism. All of it is based on simple mathematical formulas and geometry. The result is a new kind of machine.

Now, to create realistic and beautiful images or videos, you do not need a camera, an artist, or an animator. A few words of text are enough.

This text, compiled by eb43.github.io, is based on the story by Welch Labs.